The growing list of countries expressing interest in BRICS membership highlights the bloc’s increasing appeal. Several prominent economies from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), including Thailand, Vietnam, and Malaysia, have shown interest, while nations seeking European Union membership, such as Turkey and Serbia, are also considering this alternative.

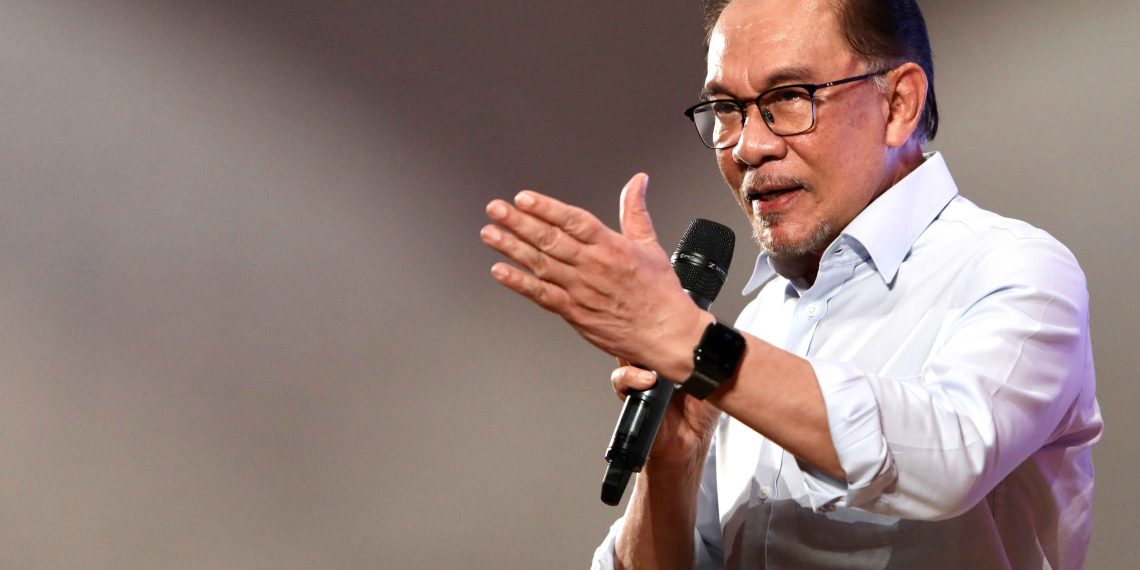

Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim recently voiced his country’s eagerness to join BRICS, citing concerns about currency stability and the limitations of a Western-dominated global financial system. In an interview with Chinese state media, he lamented the depreciation of Malaysia’s currency despite achieving record-high investments. He questioned why Malaysia should continue using the dollar for trade with other emerging economies. With its robust industrial economy, significant natural resource exports, and role as a hub for Islamic banking, Malaysia could be a valuable addition to BRICS. The strategic Strait of Malacca further enhances its importance, handling around 40% of global trade.

Joining BRICS could enable Malaysia to expand trade opportunities, reduce tariffs, and attract investments, especially from economic giants like China and India. This step could elevate Malaysia’s strategic influence while bolstering the bloc’s control over a crucial Pacific trade route.

Turkey is also exploring BRICS membership, following years of stalled EU accession talks. Though a member of the Council of Europe and the EU customs union, Turkey’s prospects for full EU membership remain dim. Its interest in BRICS reflects frustration with EU bureaucracy. Turkey is the largest non-BRICS and non-G7 economy by purchasing power parity after Indonesia, playing a critical role as a regional power with 50,000 vessels and a significant share of global wheat trade passing through the Bosphorus.

For Turkey, BRICS membership could aid its battle against inflation by promoting trade in local currencies and attracting investment from major developing economies. It could also provide Turkey access to BRICS financial resources, including the New Development Bank. The move aligns with President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s push for economic autonomy and reduced dependency on Western influences. This strategy has taken on greater urgency as Turkey’s relations with its NATO allies have become strained, especially regarding support for Kurdish groups in Syria.

Serbia, another potential BRICS candidate, has faced frustration over EU membership requirements, particularly demands to recognize Kosovo’s independence. This has created a rift between Belgrade and Brussels. Serbian Deputy Prime Minister Aleksandar Vulin has highlighted the advantages of BRICS over the EU, noting that BRICS operates as a loose association, offering flexibility compared to the stringent conditions imposed by the EU. According to Vulin, Serbia views BRICS as a viable alternative for economic cooperation, especially given the country’s decision to maintain neutrality in the Ukraine conflict.

Despite pressure from Western powers, Serbia continues to engage with both Russia and the EU. Vulin suggested that Serbia’s stance might expose President Aleksandar Vucic to risks, such as potential unrest aimed at altering the country’s political course. He pointed to other leaders who have faced repercussions for advocating peace in Ukraine.

While it remains uncertain whether Malaysia, Turkey, Serbia, or other interested nations will be invited to join BRICS at the upcoming summit in October, the growing interest indicates a vote of confidence in BRICS’ efforts to foster a multipolar world. For many nations, joining the bloc offers an opportunity to pursue economic growth, financial stability, and enhanced international cooperation outside the traditional Western-led frameworks.

Prime Minister Anwar’s comments on Malaysia’s currency challenges underscore the broader sentiment driving interest in BRICS, as countries seek alternatives that better align with their economic priorities and aspirations.